Rising costs and irregular incomes strain basic needs, making predictable support essential.

Social assistance provides non-contributory cash or in-kind transfers that stabilize household consumption through cash transfers, school feeding, public works wages, and social pensions.

Your decisions improve when the differences between social insurance and labor programs are clear, eligibility rules are mapped, and application steps are prepared in advance.

What Social Assistance Covers

Social assistance refers to direct, regular, and predictable transfers in cash or in-kind that raise and smooth household income without any contribution from recipients.

Typical instruments include cash transfers, social pensions, school feeding, in-kind livelihood packages, and public works wages paid in cash or food.

Financing usually comes from general taxation, sometimes complemented by donors in lower-income settings.

How It Differs from Other Pillars

Social insurance requires contributions and primarily covers life-course risks such as old age, unemployment, maternity, or illness, often tied to formal employment.

Labor market programs protect workers’ rights and help jobseekers through job centers, training, and wage or standards regulation.

Many poor people work informally, so non-contributory assistance remains the primary entry point for protection in developing contexts.

Social Protection Matters Now

Recent evidence points to high returns when transfers are well designed and well delivered. For every dollar transferred to poor families, local economies can see roughly $2.50 in activity due to multiplier effects.

Despite scale-ups during COVID-19, about two billion people remain uncovered or inadequately covered, and three in four people in low-income countries still lack basic protection.

Emerging Economies

Labor markets face a mounting youth bulge in emerging economies, where expected job creation trails demographic pressures.

The World Bank Group reports support to more than 222 million people across 72 countries and, as of April 2025, finances about $29.5 billion for social protection and labor, including $15.5 billion via IDA, while targeting 500 million people reached by 2030.

Pillars of Social Protection

Tight budgets and uneven labor markets make it important to match the instrument to the risk profile and delivery capacity.

| Pillar | What it is | Typical instruments | Common constraints |

| Social assistance | Non-contributory transfers for poor or vulnerable groups | Cash transfers, social pensions, school feeding, in-kind support, public works | Targeting errors, delivery costs, fragmentation |

| Social insurance | Contributory risk-pooling across participants | Pensions, unemployment, health, disability, disaster insurance | Excludes informal workers without subsidies |

| Labor market programs | Measures that promote jobs and protect worker rights | Job centers, training, SME policies, minimum wage, safety standards, maternity and sickness benefits | Limited reach in informal economies |

Major Social Assistance Programs

Households face different risks across the life cycle, so program menus work best when coordinated and sequenced for the same families.

Social Transfers (cash)

Cash transfers can be unconditional or conditional and targeted or universal. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) tie benefits to school attendance or health visits to build human capital.

Example Countries

Country examples include the Philippines’ Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program using proxy-means tests to reach extremely poor households.

Indonesia’s Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), which links payments to maternal and child health and schooling while coordinating with rice subsidies (Raskin), education aid (BSM), and health coverage (Jamkesmas).

China’s Minimum Living Allowance (Dibao/MLA) is a large unconditional transfer with thresholds set locally for urban and rural areas, though inclusion and exclusion errors have challenged accurate targeting.

Child Welfare and School Feeding

Programs range from cash- or food-for-education schemes to universal school meals and specialized services for orphans or street-connected children.

Afghanistan’s food-for-education and Cambodia’s school feeding increased attendance and improved nutrition, with take-home rations proving attractive for families and supportive of girls’ education.

Disaster Relief

Rising climate and disaster risks have pushed relief to a larger share of assistance portfolios.

Bangladesh’s Vulnerable Group Feeding and cash for housing repairs illustrate rapid support following cyclones and floods. Anticipatory and preventive measures improve outcomes, yet many systems still tilt toward ex-post response rather than risk reduction.

Social Pensions

Non-contributory pensions protect older people who lack formal coverage.

Nepal’s largely universal scheme for those 70+ boosted basic consumption and reduced administrative costs, while Bangladesh’s age- and income-tested allowance improved dignity and household nutrition despite modest benefit levels.

Health Assistance

Non-contributory health support often serves as a ramp to universal coverage.

Viet Nam’s Health Care Fund for the Poor integrated into national health insurance, bringing poor and ethnic minority households into similar benefit packages as formal workers.

Indonesia’s Jamkesmas aimed to insure the poor and near-poor at scale, though eligibility awareness and access barriers limited full take-up.

Disability Programs

Coverage remains the smallest across assistance types despite rising need as populations age.

Some countries, such as Japan and Uzbekistan, allocate significant spending to disability benefits, yet many systems in the region reach only a small fraction of eligible people.

Expansion requires both financing and robust disability assessment and service linkages.

Application Criteria and Eligibility Assessment

Program entry usually rests on objective, reasonable, and transparent rules aligned with non-discrimination standards.

- Means-testing compares household income and assets to a threshold, sometimes excluding specific grants or scholarships from the income calculation to avoid penalties for vulnerable groups.

- Demographic targeting focuses on household composition, pregnancy and early childhood, school-age children, older persons, or disability status, and can include migrants or indigenous communities when policy prioritizes those groups.

- Employment-linked screens may prioritize the working poor or structure benefits to avoid discouraging transitions into formal work.

- Conditionalities require actions such as regular health check-ups or verified school attendance, and they work best when clinics and schools exist and are accessible.

Design Choices That Affect Impact

Targeted schemes can direct scarce funds to the poorest but incur higher administrative and monitoring costs and risk exclusion errors when incomes fluctuate or documentation is weak.

Universal or categorical schemes cost more per capita at scale but cut errors, reduce stigma, and can be simpler to administer, as seen in Nepal’s pension. Conditional transfers can shift behavior if supply-side services function; otherwise, conditions punish families for gaps beyond their control.

Proxy-means tests, community validation, and grievance redress combine well to balance accuracy with fairness. Human rights principles require equal treatment, clear criteria, and accessible appeals.

Financing, Delivery, and Scale

Reallocating budgets away from regressive subsidies toward targeted transfers increases equity, and evidence suggests redirecting cash away from top earners could fund nearly half of benefits for the bottom quintile.

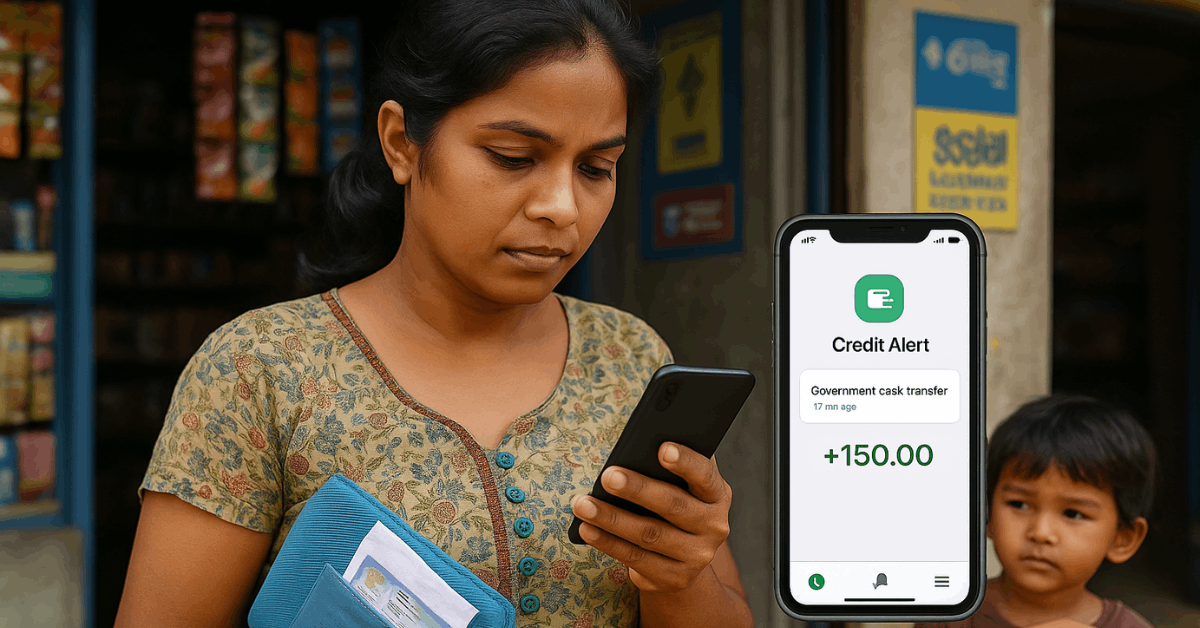

Blended and innovative financing can complement domestic revenues where fiscal space is tight. Digital delivery, ID-linked social registries, mobile payments, and interoperable management information systems reduce leakage and travel costs for beneficiaries.

Partnerships that align assistance, insurance, and labor programs create coherent pathways from relief to self-reliance, including skills, job intermediation, and enterprise support for workable households.

Getting Started: Steps to Apply

Complex rules and paperwork create barriers, so a short checklist helps you prepare efficiently.

- Identify the program that matches your profile and objective, then confirm official eligibility rules and required documents on the government portal or at a local social welfare office.

- Assemble core proofs, identity, household composition, address, income or proxy documents, and include disability certifications, pregnancy records, or school IDs where relevant.

- Register through the designated channel, submit accurate information, and keep copies of all forms and receipts to simplify follow-ups and recertification.

- Meet any conditions tied to the benefit, arrange clinic visits or school attendance tracking early, and use grievance channels promptly if an application is rejected or benefits are interrupted.

- Update records after changes in family size, employment, residence, or income to avoid suspension for mismatched data during revalidation cycles.

What to Prioritize?

Program coordination matters as much as program choice. A single household often benefits most when cash support, school feeding, and health coverage are sequenced deliberately and linked to job services once basic stability returns.

Strong delivery systems, fair rules, and predictable financing convert temporary relief into lasting gains in human capital, resilience, and participation in labor markets.

Conclusion

Coordinated, well-targeted assistance protects immediate consumption and builds human capital when payment systems, registries, and appeals function reliably.

Maintain accurate attendance and compliance records, report life changes promptly, and combine transfers with health, education, and job services to move from relief to stability.

Consistent rules, predictable financing, and efficient delivery convert limited budgets into measurable gains for families and local economies.