From the high-pitched yips of terriers to the melodic barks of Finnish Spitz, vocalization varies dramatically across breeds.

While environment and training play roles, scientific research highlights a strong genetic component underpinning differences in bark frequency, tone, and context.

This article explores how genetics, domestication, anatomy, and breed history combine to shape why some dogs are chatterboxes while others go relatively quiet.

Domestication: Where Barking Began

Barking is primarily a juvenile wolf behavior, seldom carried into adulthood. In contrast, domestic dogs bark frequently and in many contexts.

Ethologist Csaba Molnár (Eötvös Loránd University) posits that humans selected for juvenile traits—including barking—through domestication.

Just as humans favored friendly, non-aggressive wolves, so too did we favor pups who barked to alert or engage. This neotenic trait was retained into adulthood.

Molnár's acoustic studies show dogs’ barks betray emotion and intent, and humans understand them reliably wired.com.

Genetics of Vocalization: Breed-Specific Roots

Research into canine genetics demonstrates that behavioral traits, including barking, are heritable.

Genome-wide studies linking traits such as excitability, attention-seeking, and yes—barking confirm a substantial genetic basis.

Historically, selective breeding encouraged vocal traits: Scott & Fuller (1965) concluded that bark thresholds are dominant alleles, capable of being passed on.

Breed Purpose = Vocal Propensity

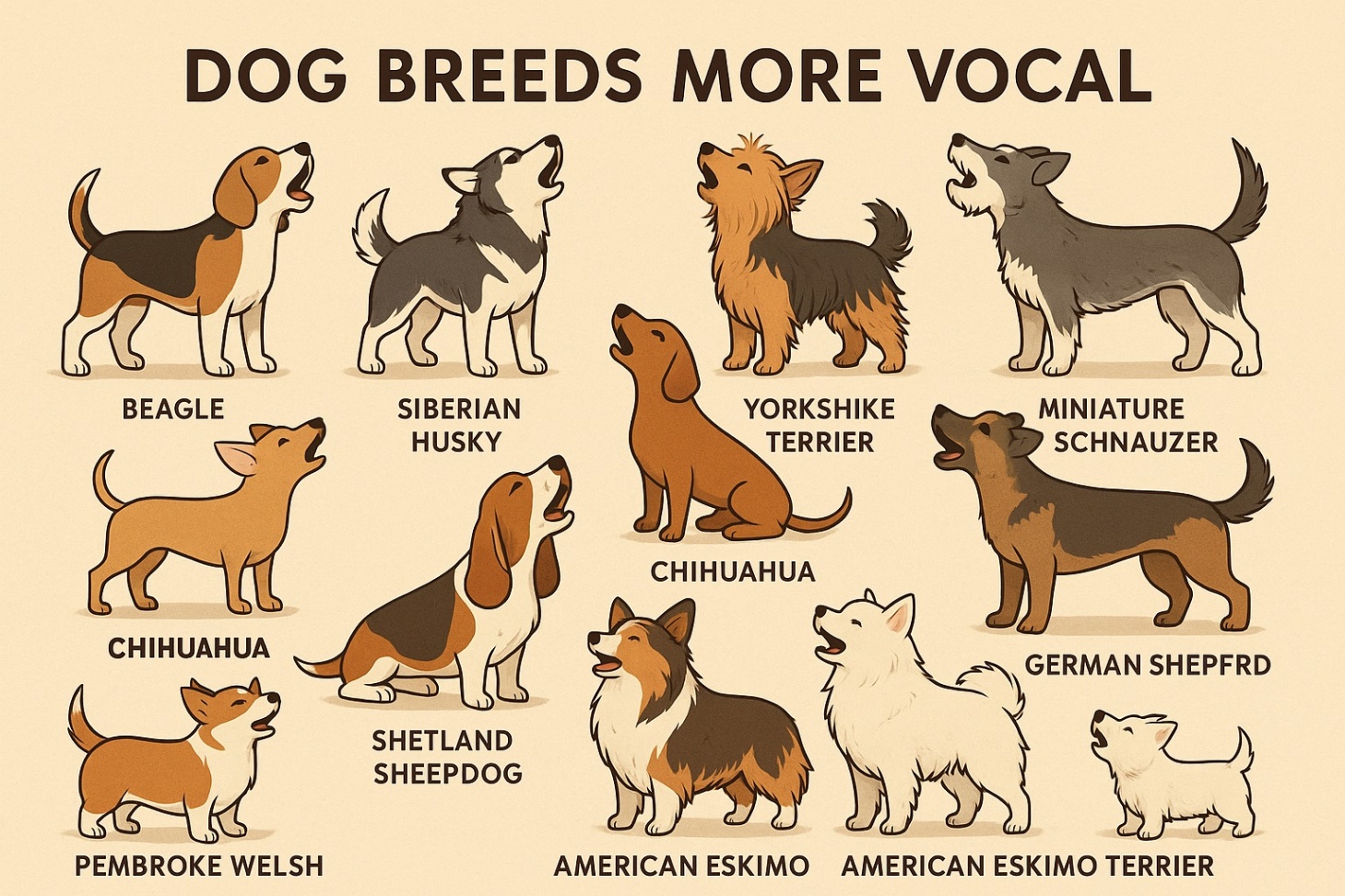

Selective breeding for specific roles also shaped vocal behavior. For example:

- Herding breeds (e.g., Border Collies, Shelties) were selected to bark to alert handlers to livestock movement: they are genetically wired to be vocal.

- Hunting breeds like the Finnish Spitz and Laika serve as “bark pointers,” using barks to indicate prey and guide humans. Finnish Spitz are known to bark as fast as 160 times per minute en.wikipedia.org.

- Conversely, stealth hunters such as sighthounds (Greyhounds, Afghan Hounds) and silent breeds like the Basenji minimize barking, reflecting evolutionary pressure for quiet hunting thesprucepets.com.

- Longevity breeds like the Basenji evolved a unique, yodel-like vocalization due to specific laryngeal anatomy, showing how genetics and physiology combine in vocal phenotype en.wikipedia.org.

Anatomy & Neural Foundations

Breeding for vocal traits also brought anatomical and neurological adaptations:

- Vocal tract structure: Variations in the larynx and vocal cords determine bark pitch and tone. Basenji’s unusual shape leads to yodels rather than barks.

- Neural regulation: Genes expressed in the brain—especially those governing neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin—influence behavioral traits like excitability and attention-seeking, foundational to barking en.wikipedia.org.

- Gene regulators like FOXP2, critical for human speech, have analogs impacting vocal behavior in mammals. Though direct links in dogs are less studied, it's plausible that similar developmental pathways help explain breed-specific barking.

Environmental & Developmental Interactions

Genetics sets predispositions, but the environment shapes expression. Early life experiences and social exposure dramatically influence how and when dogs vocalize:

Dogs with early social training often bark less to express fear or anxiety.

Even breeds genetically inclined to bark can be trained to moderate it, but underlying tendencies may require effort to manage forums.horseandhound.co.uk.

Contextual Nuance in Barking

Barking is not a monolith—barks have different structures and functions:

- Alarm barks: Sharp, short—used to alert.

- Play barks: Higher pitch and variable rhythm.

- Anxiety or separation barks: Repetitive and monotone.

Spectrographic analysis confirms predictable differences, indicating dogs use barking as a rich communication tool, not simply noisy behavior pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Case Studies of Vocal Breeds

Finnish Spitz

A “bark pointer” bred specifically to locate and hold game via bark.

Known for intense, rapid barking—up to 160 times per minute—and even competitive “king of barking” events.

Basenji

“Barkless” dog producing yodels due to a unique laryngeal shape.

A genetic anomaly reflecting its ancient lineage and hunting origins.

West Siberian Laika

A spitz-hunting dog whose very name means “barker.”

Barks aggressively when spotting prey, and without purpose if left understimulated.

Norwegian Elkhound

Hybrid of dog and wolf lineage—bred for hunting elk and large game.

Loud, assertive bark used for tracking and warning—an inherited trait emphasizing alertness.

Genetics vs. Environment: What’s the Balance?

Studies suggest that breed genetics account for around 25% of an individual dog’s personality traits.

Specific traits like barking, excitability, and attention-seeking show even higher heritability.

So while early training and environment matter immensely, genetics create the underlying canvas upon which behavior is painted.

Practical Takeaways for Owners

If barking is a concern, research breed tendencies. Quiet breeds include Basenji, Greyhound, Whippet, and Mastiffs thesprucepets.com.

Herding, hunting, or guard breeds often bark more. Know why your breed barks—and address basics like exercise and mental stimulation.

Early socialization helps curb fear-based barks. Social exposure shapes genetic potential.

Know your dog’s signals. Different barks convey alarm, play, stress. Interpreting bark context leads to better communication and management pettsie.com.

Future Directions in Canine Vocal Genetics

Ongoing research is exploring genome-wide associations for vocal traits and mapping neurological gene expression differences tied to communication.

Refining spectrographic behavior analysis by breed and context.

Understanding cross-species vocal-development pathways (e.g., FOXP2).

Unraveling how genetics meld with domestication and human interaction will deepen our insights not just into barking, but dog behavior as a whole.

Comparison of Vocal vs. Quiet Dog Breeds

| Breed | Vocal Tendency | Original Purpose | Bark Traits | Genetic/Anatomical Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beagle | High | Scent hound for hunting | Loud, persistent, baying barks | Selective breeding for tracking and alerting |

| Shetland Sheepdog | High | Herding sheep | Sharp, high-pitched alarm barks | High excitability and attention-seeking genes |

| Finnish Spitz | Very High | Bark pointer for hunting | Fast, rhythmic, “ringing” bark (up to 160/minute) | Bred specifically for vocal prey tracking |

| West Siberian Laika | High | Treeing and hunting game | Intense, targeted barking to signal prey | Spitz-type anatomy, vocal genes emphasized |

| Chihuahua | High | Companion/watchdog | Alert, yappy barking | Small body = high-pitched laryngeal tone |

| German Shepherd | Moderate–High | Herding, guarding | Deep, authoritative, territorial barks | Strong protective instincts; training matters |

| Basenji | Very Low | Silent hunting in Africa | Does not bark – produces yodels (“baroos”) | Unique laryngeal structure, ancient lineage |

| Greyhound | Low | Sighthound for silent chase | Rarely barks, quiet and calm in demeanor | Bred for stealth, not alerting |

| Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | Low | Companion | Occasional soft barks | Calm temperament and non-alerting genes |

| Shiba Inu | Low–Moderate | Hunting in Japan | Alert barks when necessary, but not overly vocal | Independent nature; less domesticated behavior |

Conclusion

The reasons some dog breeds are more vocal than others are deeply rooted in their genetic history.

You’re witnessing millennia of evolution, genetics, and mutual shaping between humans and dogs.

By understanding these influences, we can better appreciate—and coexist with—our vocal companions.